thephilosophicalbrothel

December 21, 2012

Reading 2012

So I just was looking for a PDF of the first volume of Proust online because: Proust. Above the first few words of the Moncrieff translation was a sponsored ad for nasal strips. “Can’t fall asleep?” the ad said. “Try “Breathe Better Nasal Strips!” Breathe better, sleep better!” And that sent me into a vortex of counter-history–I mean, what if Proust had those nasal strips to add to his armature for sleep, his cork walls and covered windows and special underpants? What if Proust could sleep?

These are some of the books that kept me up this year. In the summer, I finally finished “War and Peace.” I’ve picked it up several times before, and I love “Anna Karenina,” but “War and Peace” has always conquered me. There’s that Woody Allen joke—“I took a speed-reading course and read “War and Peace” in twenty minutes. It involves Russia.” It’s one of those books that wants you to clear your schedule or break your leg; you need to be forcefully immobilized for a while, and preferably a little feverish so you can drift into that snowy, strange world. I’m sure that reading it in the Richard Pevear and Larissa Volkhonsky translation made all the difference this time. Parts were still slow going, especially the last forty or so pages (did anyone ever care so much about the relationship between necessity and free will in history, I would myself just split the difference, tomato, tomah-toe, if you know what I mean). I couldn’t figure out if I was supposed to like any of the main characters—if anything, I found them less sympathetic after what seemed to be presented as their redemptive maturations. I was sad when Natasha became fat and domestic. But certain scenes will stay with me forever—Nikolai in his first battle, Pierre during the sacking of Moscow. And finishing it gave me a definite sense of accomplishment. So there it is. I read “War and Peace.” You should read it, really.

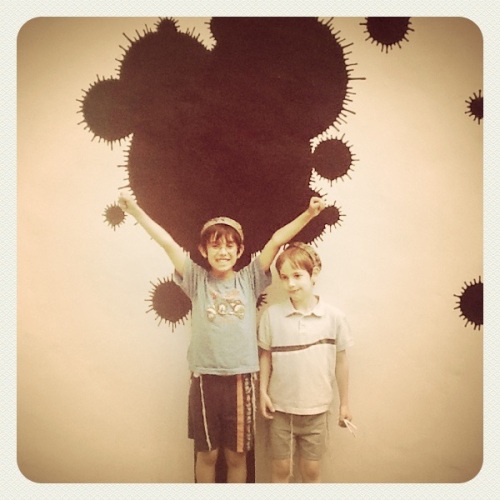

The other odd thing about reading “War and Peace” in the summer was that we were reading Tolkien to the boys at the same time, and in my dreams I kept confusing them. Prince Andrei is going to Isengard! Prince Andrei is going to Isengard! Sometimes any epic battle will do.

The other best reading project of the year was re-reading Edward St. Aubyn’s first four Melrose novels, and then finally reading the end of the quintet, “At Last,” which was published in 2011. I devoured them one after another, compelled by his articulate and witty viciousness. He writes sentences that are as beautiful and brittle as your own eggshell heart. The books are lurid and voyeuristic and uncomfortably hilarious, and detail the collective self-immolation of the late-decadent English aristocracy. They’re over the top, but they have no other choice. If you love language, you’ll love these books.

I’m pretty sure I haven’t read my favorite new book of 2012, Alice Munro’s “Dear Life.” She can do no wrong in my eyes. I’m just addicted to that subtle ache, and I’m grateful she exists. Other than that, most of the best new books I read this year are already quite celebrated, so I’m adding my voice to the chorus. Hilary Mantel’s new Cromwell book, “Bring Up the Bodies” is an immersive, full-bodied read—I don’t think I read a more satisfying book this year. The woman has found her subject. Chris Ware’s “Building Stories” is a beautiful object and a gorgeous story. I heard him speak at the D&Q anniversary event this year, and I don’t think that I’ve ever heard anyone at once so preternaturally articulate and so authentically modest. I read “Behind the Beautiful Forevers,” and it might be as good as everyone is saying. I really wanted Junot Diaz to finish the eighties-apocalypse novel that he abandoned for his new short story collection, “This is How You Lose Her,” but I’ll take the collection as compensation. Rajesh Parameswaran’s first book “I Am An Executioner” is smart and ambitious and adventurous in a way that makes you realize how narrow and constrained most short-story collections are these days. I hate-loved Sheila Heti’s “How Should a Person Be”—a deliberately ugly, awkward and compelling book that left me thinking a lot longer than lovelier and lighter fare, and that had James Wood at the New Yorker pulling out his hair with frustration. I loved the first half of Zadie Smith’s “N/W” and watched with horror as it spiraled into incoherence. One wants so much to love Zadie Smith, but I think she’d be a better writer if she wasn’t always trying to be the best student in the class. And Michael Chabon’s new book is as embarrassing as a middle-aged man who wants to show you his really awesome jazz collection. I’m pretty sure it’s the book Lev Grossman is talking about in what might be the nastiest and most cowardly review you will ever read.

Happy solstice and happy New Year, dear readers! The world won’t end today. But tomorrow, the days will begin to get longer.

November 28, 2012

Black Friday/ Buy Nothing

On Sunday morning I woke up to the news of the factory fire in Bangladesh. At least 111 are dead, and some are still missing. The tragedy is being compared to one of the worst industrial disasters in American history, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which claimed the lives of 146 victims, many of them Jewish and Italian immigrants, most of them women. Like the employees of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the victims at the Tazreen Fashions factory were primarily women, who dominate garment industry production worldwide; the building had insufficient fire exits, so workers fled to upper floors to escape the fire, and some jumped to their deaths. Tazreen Fashions supplied Walmart as recently as May 2011, when it was cited for safety violations. Walmart claims it no longer uses Tazreen as a supplier, but confirmed that one of its suppliers had “subcontracted” back to Tazreen without authorization. The Nation has photos of Walmart clothing in the debris of the fire. The inquiry that followed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory disaster resulted in significant changes for factory standards and worker safety: better exits, mandatory alarms and sprinkler systems, shorter hours for women and children, and the growth of labor unions that further protected worker safety and rights. What changes will come out of the tragedy in Dhaka, where labor is so cheap that even China has begun to outsource production to Bangladesh?

In other weekend news, two men were shot outside a Walmart in Tallahassee, Florida, in a fight over a parking spot. In Atlanta, outside another Walmart, a shoplifter was throttled to death by a security guard for shoplifting. Spending over the weekend hit 52.4 billion dollars. And people bought, you know, a lot of stuff.

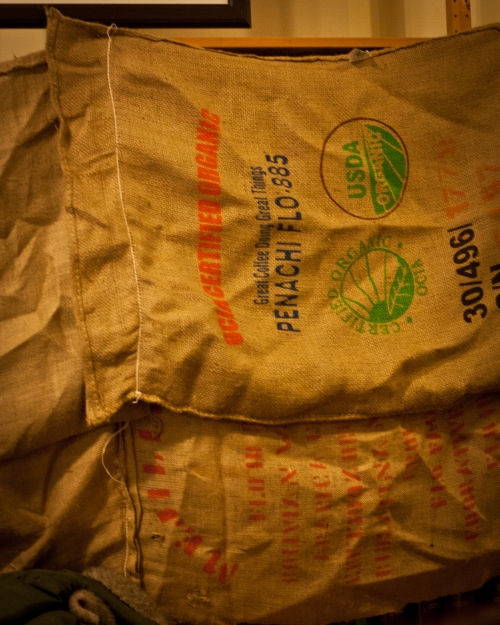

Buy Nothing day corresponds to Black Friday, and serves as a boycott of consumer culture on the day when we’re likely to consume most flagrantly. At my local co-op, Buy Nothing day is observed on Sunday, rather than Friday, so they can turn the entire day into a celebration. The shelves are covered in burlap, the staff serves free cake and coffee, and local musicians come and play music. I’ve been going for years, and besides the obvious benefit of feeling less anxiety about the chain of supply I’ve watched a community grow around the place. Children that I met at the co-op as infants will be entering high school next year.

Changing consumption habits is difficult because products just leap into your hands; I mean, you walk down the street and bargains throw themselves at you, they stick to you like burrs in the woods. It isn’t that you seek them out, it’s that you need to constantly be turning them away. They call your name, they come into your email box, they say, like the old lusts in Augustine’s confessions, do you really think you can live without us? I’ve made some small changes, and even those can be a struggle to keep. We don’t shop at Walmart, though that’s as much to do with a hatred of driving and big box shopping as it has to do with ethical consumption. I’ve started to purge my email of some of those panders, the groupons and living socials, so that I don’t invite temptation, or slip and fall into a four hundred thread count sheet set or a weekend up North. Since last Spring, when shopping for myself, I’ve only bought used clothes or clothes that are locally made. I don’t mean to be shrill or smug—god knows I’m still drowning in stuff, and the most ethical kind of consumption is to simply buy less. I’m going to keep that in mind this holiday season, as I walk around like a grinch on Wordsworth muttering to myself, “Getting and spending we lay waste our powers.”

Besides, there are powerful compensations to turning your face away from big-box store bulimia: supporting local businesses, developing relationships with people in your neighborhood, buying quirky or original gifts that aren’t mass-produced, creatively repurposing clothes that other people have discarded, taking it grandpa style. You could shop used and local because it’s the right thing to do, or you could just do it to be fabulous.

November 16, 2012

Movember of my soul

Oh November, what have you done to us! The light is vanishing and the days are getting colder. The leaves have fallen off the trees, the sky is the color of bone, and all across the city men have begun to sport uneven growths on their upper lips. Is it the last refuge of manliness in a feminized world? Pink ribbon envy? An excuse for silly facial hair? Much as I’d love an exposé of the prostate cancer industrial complex (brownwashing?) instead I’ll direct you to J.’s fundraising page. Support men’s health and marital discord.

Of course we have more important things on our minds. I’m going to start with the hurricane. We caught the very edge of the storm in Montreal. I fell in love with New York hard when I lived there in the nineties, and I have many friends who live there still. I’ve been teaching Ovid this week and I was struck by this description of the flood. Here it is, in the Rolphe Humphries translation (I like Jorie Graham’s version even better, but it’s not at hand).

Ugly sea cows

Float where the slender she-goats used to nibble

The tender grass, and the Nereids come swimming

With curious wonder, looking, under water,

At houses, cities, parks and groves. The dolphins

Invade the woods and brush against the oak trees;

the wolf swims with the lamb; lion and tiger

are born along together; the wild boar

finds all his strength useless, and the deer

cannot outspeed that torrent; wandering birds

Look long, in vain, for landing-place, and tumble,

exhausted, into the sea.

Some of those photos of New York–the parking lot of taxi cabs bobbing like dead goldfish, the black streets, the broken-necked crane–have that same surreal serenity. I wish you clear skies, New York, and a quick recovery. And for all of us: this may not be a message from the gods, but we’d be wise to take it as one.

And the election! What a relief. To turn to Ovid once again:

Now Gaza. I’m aching for those on both sides of the border who will suffer in this conflict. I’m not interested in assigning blame, arguing about who started it, discussing proportional response, or looking at your atrocity pictures on Facebook. I just want it to be done. The night before memorial day, B. disappeared into his room. He came down at 11 the next morning and read this poem to me solemnly.

The poppies whisper as you pass.

Shining red in the green grass.

They whisper of the earth’s great wish

a wish for man, trees, birds and fish.

A wish for peace, for us to understand

what war has done to this green land

For only then when we all realize

war will go away, immaterialize.

The poppies whisper one by one

for those who died from what war has done.

My son at 10. Pacifist. Poet. And able to (correctly) describe the cadences of the fourth line as Seussian.

There may be hope, even for us. Still: natural disaster; political near-disaster; war; and to quote that ubiquitous HBO series winter is coming. Can I be blamed for feeling a bit apocalyptic? At Atwater market at two in the afternoon the sky was already turning pink and it felt like I was watching the sun set into the end of the world.

September 12, 2012

Spoiler Alert: The Nazis are Coming!

We were watching The Sound of Music last night, which has lost none of its power to captivate over the last fifty years, even though it clocks in at three hours and overuses a misty soft focus on every single close-up meant to evoke fantasy or desire (B. said, why does it look so blurry? Because desire is blurry, my love, at least in the cinematic conventions of 1965). We were almost at the end, after the Austrian pomp and shrieking organ music of the wedding, and I said, “Uh, oh, now the Nazis are coming.” “Spoiler alert!” L. said, “the Nazis are coming!”

Last year, on a spring evening that felt like winter, B. came home and asked me to help him with his homework. “I have to ask you a question,” he said, and I said, “Go ahead.” He was standing on the stairs, with a piece of pencil and a paper. He said, “I have to interview people in my family. If you had to leave the house in a hurry, and you could only take a few things with you, what would you take?” I looked at him hard. “Is this for the holocaust unit in your class?” I said. He sighed and looked back at me and said, “Are you going to talk disapprovingly about this to Abba tonight when you think I’m asleep?” He was starting to panic, because he is the kind of child who panics when there is some obstacle in between him and a teacher’s demands. “All right,” I said. “Money. Passports. You boys. Warm clothes. A couple of pictures.” “The iPad,” L. said, and I said, yes, I’d take the iPad. I was starting to warm up to the list, despite myself; it wasn’t like I’d never considered the question before. L. had a similar list, except that he wanted to take his lego, but just between you and me there’s no way he’s taking his lego. That would only slow us down as we hiked the mountain passes between Austria and Switzerland.

Aren’t they too young? When L. was born a friend gave us a children’s book–a picture book, beautifully designed. The book was about a baby thrown out the window of a train during a transport to a Nazi death camp. The baby is found and saved by a local woman, and lives to survive the war and tell her story. There it is, on the tenth page, the baby swaddled in pink in a black and white world, flying out the window of the cattle car to the deserted road beside the tracks. I hid that book. I didn’t want to give it away because I didn’t want it to end up in the hands of some other child. That is not a story for children. How soon do we want to give our children nightmares? Beckett said, we can’t escape the past because the past has deformed us, or has been deformed by us. I can’t pretend to know what to do about this. The book is still stashed in my closet.

The morning after his homework assignment B. looked pale and worried. He’d had a nightmare about pursuit. I wrote to his teacher and said: do you realize your curriculum is giving nightmares to nine year old children? She wrote back to me right away–in fact, she must have written to me from school–and she said she’d talk to the children again that day. When I picked B. up to go home, he was radiant. “Guess what?” he said. “Other children are having nightmares too!” He was so happy, I mean, it made him feel so much less alone.

September 3, 2012

Road Trip

I took August off, like the therapists. We went West. God, the effortful good cheer of road trips. Come on kids, get in the car!

We drove for hours up terrifying roads to obscure places and when we arrived we always found parking lots full of cars and Chinese grandmothers with big hats and dark sunglasses. If my pictures were honest, there would be a crowd of people in half of them, elbowing each other out of the way for an uninterrupted view of the personal sublime.

On the Icefields Parkway, signs hectored us with a polite mantra: “When you approach or feed an animal, you are taking away its wildness, and that is the most precious thing about it.” I was stuck on that phrase–what was the quality of wildness, that you could capture it? Why was wildness described as a most precious possession? If it was something you had, was it also something that could be taken away? Addled, antifreeze-addicted bighorn sheep nuzzled our car–come on, come on, man, just a lick, just a lick. We saw a bear cub ambling off the road, and tourists on the roadside jostled to take photographs. Majestic elk acted majestic. You are taking away my wildness.

Eleanor Roosevelt said scare yourself every day. J said, scare your mother every day. I was bred for caution, not for daring. Signs on the road warned us of all the ways we might die: avalanche, elk crossing, dangerous curves ahead. The trail was closed for “wolf activity.” We traveled in tight groups of four, and sang songs to keep the bears away. Tall rocks invited clambering, and small crevices invited broken ankles. We ate tiny wild strawberries that tasted of wine and earth.

We tricked the boys into a hike up the Cavell meadows. They talked about cards the entire time. As we left, we heard a sound like tearing, like thunder, like your own teeth grinding in your own skull, and as we looked back a piece of the glacier had sheared off and fallen. It only lasted as long as a held breath. B said, I’m going to tell that to my grandchildren. When we left the parks our eyes had to get used to the trash and clatter of billboards on ordinary highways. We had seen only beautiful things for so long.

The Athabasca glacier reminded me of a rhinoceros I once saw at the Bronx Zoo. He was massive, indifferent to our stares, and nearly immobile. Signs mark the land the glacier once held, and where it retreated it has left only barren and rocky moraine. We said we were on the glacier extinction tour. The crowfoot glacier has lost a claw. The angel glacier is losing a wing. The angel glacier is losing a wing. Do you need a clearer sign?

July 19, 2012

The Clock

If I was in New York this weekend, I’d be going to see Christian Marclay’s video piece ‘The Clock’ at Lincoln Center. I watched about an hour’s worth last summer at the Venice Biennale, and even though I’d read about the central conceit of the piece several times–Marclay collages 24 hours worth of film, with a clock or some explicit time cue in each fragment, so that you move in real time through the history of cinema and through a patchwork meditation on time’s meaning and passage–but somehow I still experienced that shock of recognition, the uncanny sync of the time on my wrist and the time on the screen. The piece is a miracle of editing and a weirdly intoxicating experience. As the screen faded out a very young Denzel Washington and then faded in Paul Newman it struck me how much our time is the time of celebrity; the faces of certain actors bring back entire phases of my life, like a Proustian madeleine consisting of dated haircuts and half-forgotten names.

I have this bad habit of being prematurely elegiac (umm, hello new Mirror?). That means that even though it is still July, I already have a bloodhound sense of summer fading. Really, I’m happiest in the period right before the summer solstice, when we haven’t yet reached the very longest day. Everybody tells you that when you have children time passes more quickly, and what I remember best about Zadie Smith’s article on ‘The Clock’ from last year is her envy at all the childless gallery-goers who can stay and watch all night. Time passes faster now.

I’ve also been watching a lot of Louis CK, who is the Rembrandt of comedy in that his great subject is aging and the decay of the flesh. He talks about his kids all the time, and their innocence and youth is the counterpoint to his cynicism and age. B. turned ten this year, a thing I cannot say without incredulity. Youth belongs to him, but I don’t mind. A friend of mine just bought a house with a running track behind it. He says he is going to run there with his daughter. She’s small now, and he’ll give her a head start, so that they reach the end of the track at the same time. As the years go by the gap will narrow, until she gives him a head start because he can’t keep up with her. Being a parent means you kind of like it when your children eclipse you. Look, they’re passing us already.

But sometimes it’s just good to feel like time is standing still, so after I saw ‘The Clock’ during my imaginary New York weekend I would head over to see the Yayoi Kusama exhibit at the Whitney. I’d never heard of her when I stumbled into a mirrored, dark cubicle in the basement of the Louisiana museum outside of Copenhagen last spring. Colored lights hung from the ceiling, and they were reflected in endless recursion in the mirrored walls and the shallow pools on either side of a narrow walkway. In all that light, my body was the shadow. The piece is called ‘The Gleaming Lights of the Souls’ and it is at once melancholy and exhilarating. I stayed in there for a long time, and people kept stumbling inside, taking a deep breath, and standing in wonder. There’s a similar piece at the Whitney, called ‘Fireflies on the Water.’ Apparently the Whitney has a strict one-minute rule about staying in the cubicle, which is too bad. No one should interrupt you while you’re communing with infinity.

July 13, 2012

Art/ Kitsch/ Kids

I’ve been trying to take my boys to art events and exhibits around town, even though I know that the result of my cultivation of their taste will be their rejection of my own. It’s starting already; I was telling them a bedside story and B. interrupted a minor but pivotal plot point (lost parent; hidden talent; birthmark) by saying, “that always happens in stories like this one.” I was stung, truly, though I wasn’t trying to be original: I was just trying to get them to go to sleep.

At FIMA the proportion of kitsch to art was high, though the kitsch had a Dali flavor (Nabokov on Dali: “Norman Rockwell’s twin brother kidnapped by gypsies in babyhood”). They had a small gallery set up just for children. Artists contributed small paintings, on sale for ten dollars each. The idea was that the children would choose a piece of artwork on their own, without parental interference or pressure. I wasn’t allowed inside and I couldn’t believe that I was sending my children into a closed room with strangers, to be given juice and candy and balloons. Art is dangerous.

We also went to the ZOO exhibit at MAC, though I probably should have waited for a time when the boys were less heat-stroked and loopy. I wanted to see Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, gaudy and contextless and lovely. These are golden copies of the animal heads designed by two nineteenth century Jesuits who lived in China and created a fountain/water clock to decorate the old summer palace outside Beijing, importing baroque design to an interpretation of the Chinese symbols. In 1860, the palace was destroyed by French and English soldiers and the fountain looted. The Chinese government continues to try to repatriate the stolen heads, which have become symbols of cultural appropriation, ownership and legitimacy.

Ai Weiwei is one of those artists who has become heroic under the pressure of the Chinese regime. He has a populist canniness and a willingness to follow his art out to its spiraling conclusions. In 2010 Weiwei had artisans in Jingdezhen hand-fire and paint one hundred million sunflower seeds, which carpeted the floor of the Turbine Hall at the Tate in London. The seeds evoked the tension between craftsmanship and mass production, celebrity art and anonymity, the history of porcelain in China and the history of hunger, fragility and multiplicity, art and oppression (in the original exhibition, people tread on the seeds until the ceramic dust was declared hazardous and the area roped off). But each was a little miracle, a bit of trompe-l’oeil that you could hold in your hand. Here is Weiwei describing the evolution of the piece:

“When the seeds began to show, people started to ask: Can we have some? I responded very casually, ‘Whoever wants some, just give me an address and I’ll send them to you.’ We received about a thousand requests. And, since then, it has become a kind of movement. We’ve sent out several hundred thousand. This is amazing. They call it the ‘Sunflower Seeds Party.’ The party can be read as a party or a Party. And young people love it. They say, ‘The girl at school I loved for so long, and I could never really speak to her, I made an earring out of a seed and gave it to her.’ Another one said, he gave it to his parents. One said the seed will be the first gift to my unborn kid. And someone else said, by the year two-thousand-and-something, the seeds will have life coming out of them. They call them seeds of freedom. It’s very interesting that people need something to carry their fantasy.”

The boys liked the zodiac heads, and they loved the fountain outside, where Trevor Green installed a urinating monkey with a serpentine neck. After that, L. kept asking me if he, too, could pee in the fountain. That seemed an oddly appropriate response. The guard looked at us nervously, as if he was enacting the contrast between irreverent art and the hands-off, breath held reverence expected of audiences of contemporary art.

As we left, we stopped to watch the Weiss and Fischli film The Way Things Go (1986). The film documents a giant Rube Goldberg machine, constructed in a large industrial studio, with components made of junk, foam and fire. The boys narrated the entire thing as though it was a sports event, anticipating each new step in the chain reaction. The thing about Rube Goldberg machines is that they are useless; their uselessness is constitutive. The end result has to be vastly disproportionate to the effort expended, so that they really are about process, not product, life as one damn thing after another. This one is so long that it’s actually boring and digressive and feels random, for all of its design. It helped me articulate what I hate about Ted talks; they are so damn teleological, in their tight, fourteen minute frames. All struggle is retroactively justified, all action is purposeful. There is no space for boredom, no time for uselessness or idleness or epistemological wandering. The Way Things Go is like a Ted talk for melancholics who don’t believe in destiny but retain a sense of wonder at the sheer, unproductive fecklessness of life. I could have watched it again and again.