Art/ Kitsch/ Kids

by amfreedman

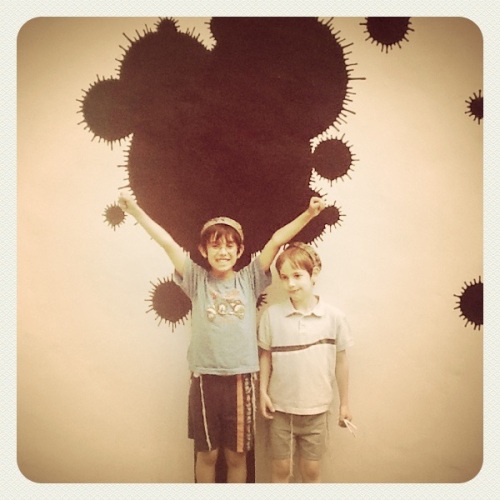

I’ve been trying to take my boys to art events and exhibits around town, even though I know that the result of my cultivation of their taste will be their rejection of my own. It’s starting already; I was telling them a bedside story and B. interrupted a minor but pivotal plot point (lost parent; hidden talent; birthmark) by saying, “that always happens in stories like this one.” I was stung, truly, though I wasn’t trying to be original: I was just trying to get them to go to sleep.

At FIMA the proportion of kitsch to art was high, though the kitsch had a Dali flavor (Nabokov on Dali: “Norman Rockwell’s twin brother kidnapped by gypsies in babyhood”). They had a small gallery set up just for children. Artists contributed small paintings, on sale for ten dollars each. The idea was that the children would choose a piece of artwork on their own, without parental interference or pressure. I wasn’t allowed inside and I couldn’t believe that I was sending my children into a closed room with strangers, to be given juice and candy and balloons. Art is dangerous.

We also went to the ZOO exhibit at MAC, though I probably should have waited for a time when the boys were less heat-stroked and loopy. I wanted to see Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, gaudy and contextless and lovely. These are golden copies of the animal heads designed by two nineteenth century Jesuits who lived in China and created a fountain/water clock to decorate the old summer palace outside Beijing, importing baroque design to an interpretation of the Chinese symbols. In 1860, the palace was destroyed by French and English soldiers and the fountain looted. The Chinese government continues to try to repatriate the stolen heads, which have become symbols of cultural appropriation, ownership and legitimacy.

Ai Weiwei is one of those artists who has become heroic under the pressure of the Chinese regime. He has a populist canniness and a willingness to follow his art out to its spiraling conclusions. In 2010 Weiwei had artisans in Jingdezhen hand-fire and paint one hundred million sunflower seeds, which carpeted the floor of the Turbine Hall at the Tate in London. The seeds evoked the tension between craftsmanship and mass production, celebrity art and anonymity, the history of porcelain in China and the history of hunger, fragility and multiplicity, art and oppression (in the original exhibition, people tread on the seeds until the ceramic dust was declared hazardous and the area roped off). But each was a little miracle, a bit of trompe-l’oeil that you could hold in your hand. Here is Weiwei describing the evolution of the piece:

“When the seeds began to show, people started to ask: Can we have some? I responded very casually, ‘Whoever wants some, just give me an address and I’ll send them to you.’ We received about a thousand requests. And, since then, it has become a kind of movement. We’ve sent out several hundred thousand. This is amazing. They call it the ‘Sunflower Seeds Party.’ The party can be read as a party or a Party. And young people love it. They say, ‘The girl at school I loved for so long, and I could never really speak to her, I made an earring out of a seed and gave it to her.’ Another one said, he gave it to his parents. One said the seed will be the first gift to my unborn kid. And someone else said, by the year two-thousand-and-something, the seeds will have life coming out of them. They call them seeds of freedom. It’s very interesting that people need something to carry their fantasy.”

The boys liked the zodiac heads, and they loved the fountain outside, where Trevor Green installed a urinating monkey with a serpentine neck. After that, L. kept asking me if he, too, could pee in the fountain. That seemed an oddly appropriate response. The guard looked at us nervously, as if he was enacting the contrast between irreverent art and the hands-off, breath held reverence expected of audiences of contemporary art.

As we left, we stopped to watch the Weiss and Fischli film The Way Things Go (1986). The film documents a giant Rube Goldberg machine, constructed in a large industrial studio, with components made of junk, foam and fire. The boys narrated the entire thing as though it was a sports event, anticipating each new step in the chain reaction. The thing about Rube Goldberg machines is that they are useless; their uselessness is constitutive. The end result has to be vastly disproportionate to the effort expended, so that they really are about process, not product, life as one damn thing after another. This one is so long that it’s actually boring and digressive and feels random, for all of its design. It helped me articulate what I hate about Ted talks; they are so damn teleological, in their tight, fourteen minute frames. All struggle is retroactively justified, all action is purposeful. There is no space for boredom, no time for uselessness or idleness or epistemological wandering. The Way Things Go is like a Ted talk for melancholics who don’t believe in destiny but retain a sense of wonder at the sheer, unproductive fecklessness of life. I could have watched it again and again.

This is really beautiful and moving. I opened it on my iPad a month ago, and haven’t read it until today (I’ve been using my laptop a lot instead). I just talked to my students about the biological value of narrative, and my whole point was that the depth and pleasure of literature immensely surpasses its usefulness–that in that sense, you might as well call it useless. What I love about what you’ve written here is that you go more directly towards that sentiment.

Thank you! What were you using to talk about biology and narrative?